From Crisis to Movement: How Schools Can Best Support Youth Mental Health

7 CommentsThis post was written by former Voices intern Abby Aquije, featured on the right in the above photo.

Responding to the Growing Severity of Youth Mental Health Crisis

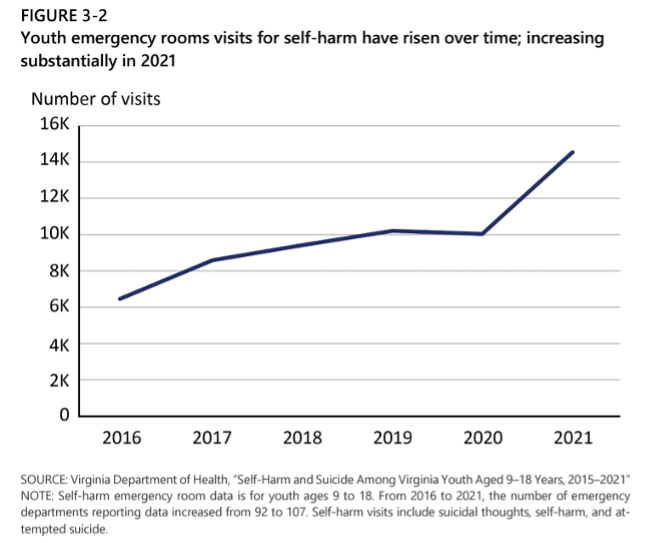

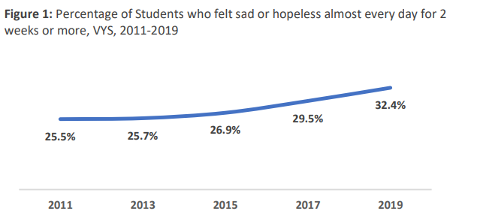

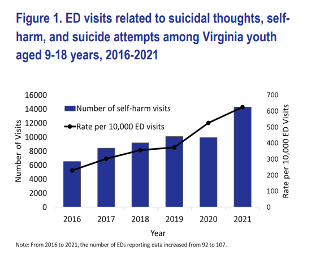

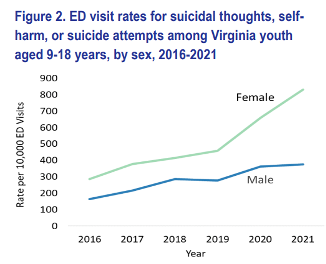

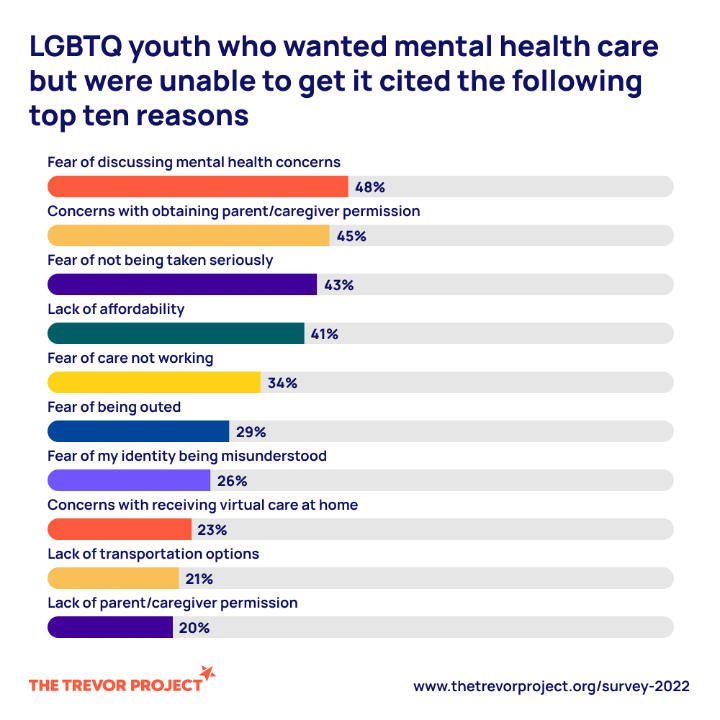

For decades we have been talking about the growing number of youth with mental health challenges, and there is an abundance of alarming statistics to support such concerns. The CDC reports that 4 in 10 students felt persistently sad and hopeless, and according to the Virginia Department of Health, the number of youth self-harm emergency department visits in Virginia is increasing. It is clear that we have reached crisis levels. Additionally, we know there are many barriers to prevention and intervention. COVID-19, negative stigmas, behavioral health care shortages, telehealth access issues, educator burnout, and more all add to the severity of this crisis. This information is well-known and widely reported, confirming the existence of a youth mental health crisis.

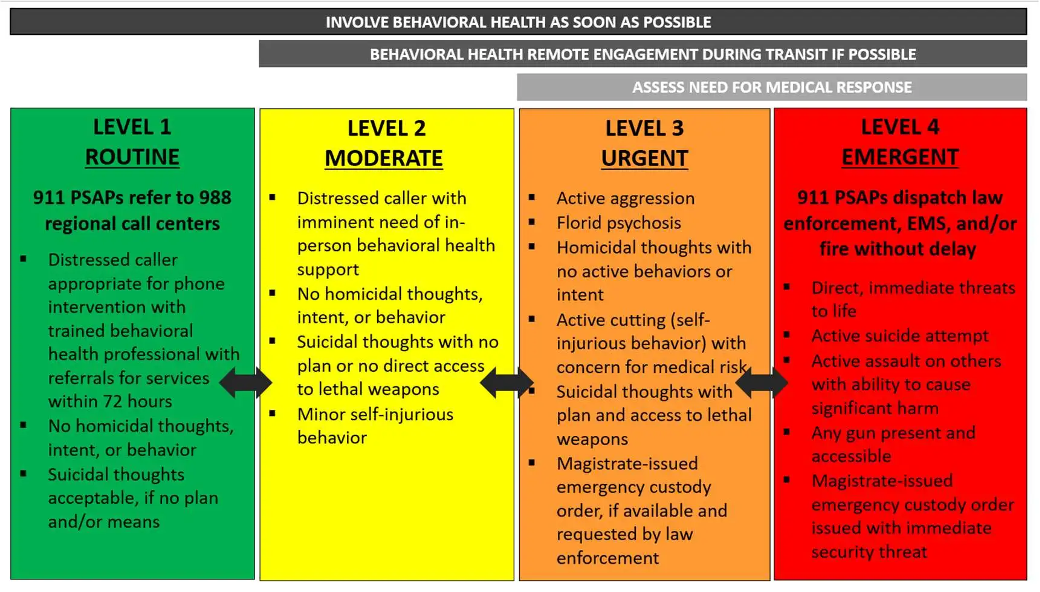

While it is important to keep these conversations going, we cannot overlook the role that youth themselves are playing in mending this crisis. As Virginia public schools are facing growing rates of “threats to self,” it is critical that education leaders and policymakers begin recognizing and leveraging students’ ability to support one another. These students are not fixated on crisis data, like many adults in the education space. Rather, they are making positive changes in how their generation interacts with mental health overall, and there is much to learn from them.

Importance of Youth Empowerment

In schools, students are listening to one another, starting clubs, and advocating for more resources, all of which all examples of youth supporting each other’s mental health. These students are passionate, capable, and motivated, and we must support their efforts, big or small.

Last year, I wrote a blog arguing for connectedness and peer support as measures to address loneliness elements contributing to the youth mental health crisis. After months of additional research on the topic and attending a Youth Mental Health Summit, I am happy to say significant youth support for this promising intervention exists. Youth are informally employing these peer support strategies already as a way to navigate challenging times, and they know the importance of promoting positive mental health practices. Their experience makes them experts on the topic, but they still need resources and adult support to engage in these actions productively, especially as it relates to peer support interventions.

School-Based Support for the Youth Mental Health Movement

Many students are engaging in mental health conversations and actions and need the training and support to do so positively. Over 85% of students with depressive behavior said they would tell a trusted adult if their friends were having mental health struggles, showing that students are motivated to support one another. Still, less than a quarter of students with lived mental health experience have received mental health training, highlighting a need for formal peer support training.

To make peer support an effective intervention, schools must provide students with mental health tools and training to engage in these conversations healthily. Providing students with mental health training allows schools to empower youth while also addressing the crisis at hand. These training programs equip students with the knowledge needed to recognize and respond to mental health concerns they see in themselves and their peers. With many barriers to identifying at-risk youth, peer support can offer a promising avenue to improve rates of early identification.

It’s important to emphasize that there is a youth-led movement to make positive changes in this area, but we cannot risk students burning out. The burden of initiating peer support, both informally and formally, should not solely fall on students. Schools need to support them as equal collaborators in addressing the mental health crisis by empowering them with the tools to support and advocate for one another early on. This means initiating student-focused interventions early on and compensating students for their time and effort. Continued engagement is critical to advancing this movement.

Abby Aquije graduated with her Master of Public Policy (MPP) from the Frank Batten School of Leadership and Public Policy at the University of Virginia (UVA) in May 2023. She is currently looking for a full-time job in the nonprofit sector.