Dr. J. Marion Simms is known as the founder of modern surgical gynecology. However, in the 1840s, Simms spent years conducting experiments on enslaved women. Their names are only known as Anarcha, Lucy, and Betsey. They were considered property and could not consent to the painful surgeries that were performed on them. In modern medicine today, numerous research studies name findings that shed light on explicitly bias beliefs that Black people have thicker skin and experience less pain. According to research by Sophie Trawalter, an associate professor of public policy and psychology at the Frank Batten School of Leadership and Public Policy, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services reported Black and Hispanic people receive worse care on 40% of the department’s care quality measures.

Research consistently describes experiencing childbirth as a significant event of great psychological importance in a woman’s life. Childbirth infinitely shapes a woman’s perception of themselves and may positively impact their relationships with other family members. However, literature only parallels the positive experience with a “well-supported, normal birth.” While healthy births are normalized, it is not taken for granted in Black communities. We have heard the horror stories of women who were not listened to by their doctors, which later resulted in death.

My niece, Genesis, was born on January 27, 2022. When I heard my sister was pregnant, I first asked, “do you have a doula? Do you have a midwife?” Many credible sources have reported a now all too familiar data point. According to the Center for Disease Control (CDC), Black women in America are three times more likely to endure death related to pregnancy and childbirth than White women, regardless of their education or financial means. For women over 30, the risk is five times higher. The Virginia Department of Health reported the maternal mortality rate for Black mothers is more than double that of White mothers. A 2019 report by the Virginia Maternal Mortality Review Team noted 44 percent of pregnancy related deaths were due to a provider related factor, such as a failure to refer or seek consultation.

The Fetal and Infant Mortality Review Team (FIMRT) Work Group Study reported Virginia’s rate of fetal death in 2019 was 7.6 fetal deaths per every 1,000 live births. While it was the lowest it has been since 2015, March of Dimes reported the infant mortality rate for Black infants was 9.5 per 1,000 live births in comparison to White infants at 4.8 per 1,000 live births in the state. (Diduk-Smith 8, 2021)

In 2021, former Governor Ralph Northam released the Maternal Health Strategic Plan to eliminate racial disparities in maternal deaths by 2025. The plan appears to be no longer available on the server, yet stated, “Black women were more likely to report experiencing discrimination or harassment due to their race/ethnicity or insurance or Medicaid status.”

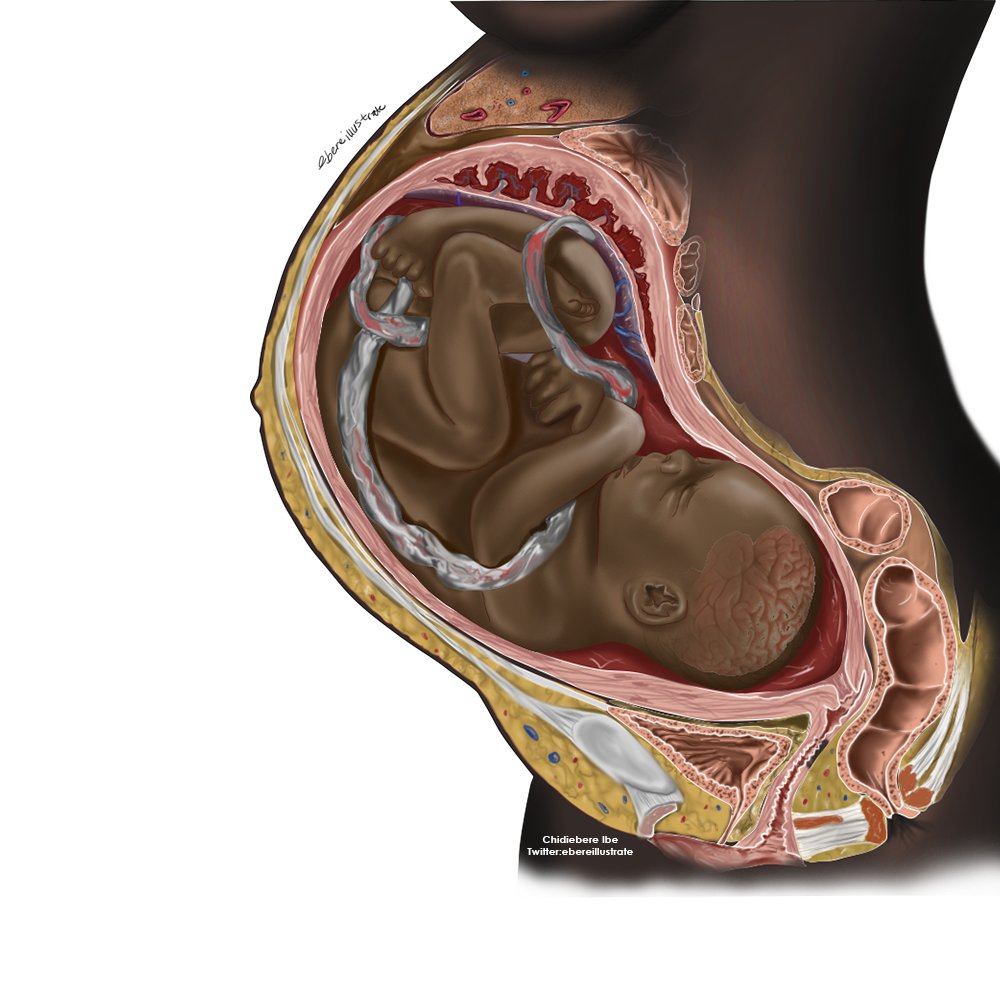

People continue to name the conscious and unconscious biases that contribute to disproportionate outcomes for Black mothers and Black babies, some of which are so endemic it goes unnoticed. In 2021, an illustration of a Black fetus in a womb went viral.

Most fetuses are reported to be red in color or dark pink and gradually develop their skin tone; however, the medical demonstration was intended to represent patients who are not used to their skin tones in such images. The illustrator, Chidiebere Ibe, responded to the virality of his illustration in a statement on CNN, “the whole purpose was to keep talking about what I’m passionate about — equity in healthcare — and also to show the beauty of Black people…we don’t only need more representation like this — we need more people willing to create representation like this.”

Black women are most impacted by maternal infant mortality disparities and it is also Black women leading the charge in dismantling them. In 2021, a Black woman, Delegate Lashrecse Aird led HJ 537, a resolution to recognize racism as a public health crisis in Virginia, making the state the first in the south to do so. The resolution included the recommendation to require training for elected officials, staff members, and state employees on how to recognize and combat implicit biases.

This year, a Black woman, Dora Muhammad, Congregation Engagement Director and Health Equity Program Manager with the Virginia Interfaith Center for Public Policy, led the initiative to require medical practitioners licensed by the Board of Medicine to complete two hours of continuing education in each biennium on topics related to implicit bias and cultural competency. While I was grateful to witness the birth of my niece Genesis, the following morning I witnessed SB 456, sponsored by a Black woman, Senator Locke, fail to report out of the Senate Education and Health’s Health Professions subcommittee with only two supporting votes from Senator Hashmi and the bill patron herself. The House version, HB 1105, also sponsored by a Black woman, Delegate McQuinn, met the same fate through a voice vote by the Health, Welfare, Institutions Subcommittee Three. These bills could have led to greater outcomes for other Black mothers and Black babies. Instead, they were put off until the 2023 General Assembly Session.

The Hippocratic Oath, “Do No Harm,” is the first commitment to becoming a doctor. While the data continues to point to disparities in maternal and infant health, there continues to be a lack of willingness to explicitly name, call out racism, or even acknowledge the possibility that racism could very much be a factor in healthcare disparities. For Black mothers, the fear of giving birth is valid. In 2020, the New York Times created a guide as a resource, Protecting Your Birth: A Guide For Black Mothers.

While Black women continue to champion change, Virginia too must commit to doing better for Black mothers and Black babies.

Resources

Diduk-Smith, PhD, MPH, Ryan Marie. Rep. Report to the General Assembly Workgroup Study: Fetal and Infant Mortality Review Team (FIMRT) HB1950 of 2021. Richmond, VA : Office of the Chief Medical Examiner Virginia Department of Health, 2021.

Humenick, Sharron S. “The Life-Changing Significance of Normal Birth.” The Journal of Perinatal Education. U.S. National Library of Medicine, 2006. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1804308/.

“Infant Mortality Rates by Race/Ethnicity: Virginia, 2016-2018 Average.” Peristats | March of Dimes. Accessed February 10, 2022. https://www.marchofdimes.org/peristats/ViewSubtopic.aspx?reg=51&top=6&stop=92&lev=1&slev=4&obj=1.

Hobron, Kathrin ‘Rosie. “Annual Report 2017 – Virginia Department of Health.” Office of the Chief Medical Examiner Annual Report 2017. Virginia Department of Health, 2017. https://www.vdh.virginia.gov/content/uploads/sites/18/2019/04/Annual-Report-2017.pdf.

Rouse, Melanie J. “Chronic Disease in Virginia Pregnancy Associated Deaths …” Chronic Disease in Virginia Pregnancy Associated Deaths, 1999-2012: Need for Coordination of Care, 2019. https://vdh.virginia.gov/content/uploads/sites/18/2019/08/MMRT-Chronic-Disease-Report-FINAL-VERSION.pdf.

United States Department of Human Services. “Racial and Ethnic Disparities Continue in Pregnancy-Related Deaths.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, September 6, 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2019/p0905-racial-ethnic-disparities-pregnancy-deaths.html.

Read More Blog Posts